The Cosmic Comic: Tom Robbins and His Enduring Legacy

Tom Robbins, the beloved author whose wildly imaginative novels captured the hearts of millions during the 1970s counterculture movement, passed away on Sunday at his home in La Conner, Washington. He was 92 years old. His death was confirmed by his son Fleetwood, though no cause was cited. Robbins’ work, which spanned decades, left an indelible mark on American literature, blending humor, philosophy, and a healthy dose of irreverence to create a unique voice that resonated with readers of all ages. His books, with their meandering plots, pop-philosophical musings, and jabs at societal norms, became a staple of the hippie era, finding a home alongside works by Carlos Castaneda, Richard Brautigan, and Kurt Vonnegut on the shelves of countercultural enthusiasts.

Robbins’ writing style was as unconventional as the times he wrote in. His sentences were often described as “cartoonish,” a term he embraced, drawing inspiration from the bold strokes of Greek myths and the exaggerated narratives of his Southern preacher and policeman ancestors. His plots were secondary to the sheer verve of his prose, and his readers adored him for it. Take, for example, this line from his 1976 novel Even Cowgirls Get the Blues: “An afternoon squeezed out of Mickey’s mousy snout, an afternoon carved from mashed potatoes and lye, an afternoon scraped out of the dog’s dish of meteorology.” Weird, nostalgic, and vaguely unsettling, it’s the kind of writing that defies easy categorization—and that’s exactly what fans loved about it.

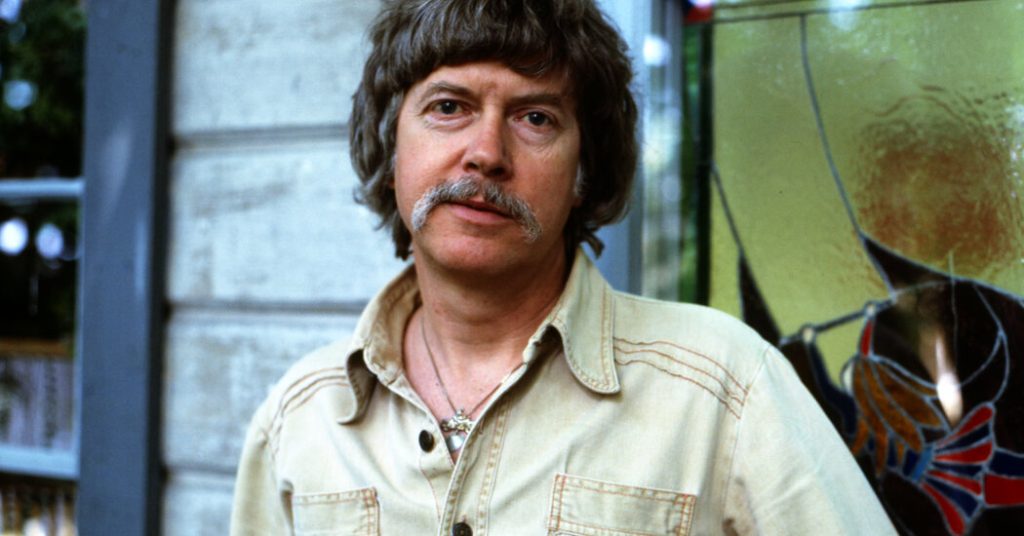

Despite his cult following and best-seller status, Robbins remained a private figure. He rarely gave interviews, shunned photographs, and spent much of his life in the small, tugboat town of La Conner, north of Seattle. His writing process was equally idiosyncratic; he wrote in longhand, agonizing over each sentence, often spending hours on a single line. He rarely had a clear sense of plot when he began a book, preferring to let his instincts guide him. “I don’t know how to write a novel,” he once confessed. “It’s a new adventure every time I begin one, and I like it that way.”

Robbins’ literary career was nothing short of remarkable. His first novel, Another Roadside Attraction (1971), was initially a hardcover flop but found its audience in paperback, selling over 100,000 copies by the time his second novel, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, was published five years later. His subsequent works, like Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas (1994) and Fierce Invalids Home From Hot Climates (2000), continued to defy expectations, blending humor, philosophy, and a healthy dose of surrealism. While critics often dismissed his work as “goofy” or “cartoonish,” Robbins’ fans saw something deeper—serious literary ingenuity masked behind a veneer of absurdity.

Robbins’ enduring appeal lay in his ability to connect with his readers on a deeply personal level. His earliest fans were the twentysomethings of the hippie era, drawn to his countercultural sensibility and his willingness to challenge societal norms. As those fans aged, they remained loyal, even as critics accused Robbins of being a relic of the 1960s. For Robbins, life was a commingling of the sacred and the profane, and he saw no need to separate humor and gravity. “I will make up my mind when God does,” he once quipped. This philosophy infused every aspect of his work, from his early novels to his later years, when he continued to write with the same philosophical goofiness that had defined his career.

Despite his literary success, Robbins’ life wasn’t without its challenges. His first three marriages ended in divorce, and he faced criticism from those who found his work too irreverent or too flippant. Yet, he remained undeterred, continuing to write on his own terms. In 2014, he published Tibetan Peach Pie: A True Account of an Imaginative Life, a memoir that offered readers a glimpse into his unconventional life. Robbins’ legacy is one of resilience and creativity, a reminder that literature can be both serious and funny, sacred and profane. As he once said, “From the outside, my life may look chaotic, but inside I feel like some kind of monk licking an ice cream cone while straddling a runaway horse.” It’s a fitting metaphor for a man who spent his life embracing the chaos of existence, one sentence at a time.